Facilitating Researcher Connections

Facilitating Researcher Connections

Promoting opportunities for peer-learning between researchers. Aiding in the formation of informal and formal collaborations. Liaising and matchmaking between users and ACI resource providers, where appropriate.

- Introduction

- Overall Strategies

2.1. Maintain Knowledge of the Researcher Base

2.2. Build Connections around Topics

2.3 Encourage Self-Sustaining Connections - Coordinate Knowledge Exchange Between Researchers

- Promote the Formation of Communities

4.1 Gauge Interest

4.2 Establish Group Goals and Format

4.3 Facilitator Participation - Formal and Informal Collaborations

- Utilize Relationships with Other ACI Staff

Introduction

A facilitator is one of the few individuals with a broad awareness of research efforts across their user or ‘client’ base. As a result, facilitators are not only poised to identify and liaise potential researcher connections and collaborations, but should feel obligated to do so. In this chapter, we discuss overall strategies for realizing common research interests and practices among researchers, as well as specific types of researcher-to-researcher interactions that a facilitator might help to initiate. This facilitation of research networks is likely to enable researchers to become more effective in their work - not just with respect to their use of ACI resources - and to pursue research opportunities or collaborations that may not have been considered otherwise. Therefore, the potential impacts of such connections mean that facilitators may indirectly enable research transformations, beyond directly working with researchers in their specific use of ACI resources.

Jump to: top

Overall Strategies

Generally, the facilitation activities discussed in previous chapters will enable facilitators to easily identify connection opportunities and to carry out the logistics of bringing together researchers for various purposes and in varying degrees of formality. However, there are additional, specific approaches that ensure the greatest potential research impact as a result of facilitator-enabled human networks. These will enable a variety of interaction types, including casual information sharing between two graduate students, to multi-member groups that meet regularly, to formal collaborations. Based upon the experiences of participating ACI-REF organizations, we describe in this section some strategies that have been successful across interaction types that are discussed later in the chapter.

Jump to: top

Maintain Knowledge of the Researcher Base

While facilitators will generally have some working knowledge of research aims and computational methods across the researchers they engage with, no facilitator can remember all details of all researcher interactions over time. As a result, there are several strategies for supplementing the facilitator’s own memory, many of which are already built into the facilitation practices described elsewhere in the Best Practices of Facilitation. For example, the notes taken by facilitators during and after engagements or assistance interactions will serve as a useful resource. If these are stored and organized for easy searching, the facilitator will be able to easily search for key terms related to the needs and interests of a researcher or group that the facilitator is currently working with. Email history (including emails within issue ticket systems) can be used in a similar way to search for key terms that connect different researchers. Even campus websites and those of specific research groups might be searched via the web.

Facilitators should generally be on the look-out for potential collaborations, especially when learning about a new researcher or group, perhaps by mentioning other researcher contacts that come to mind. Beyond real-time suggestions, the various notes kept by facilitators to record researcher interactions might be consulted just prior to or after an engagement or other interaction in order to identify researchers with complementary work. Facilitators working in a team environment can leverage the knowledge and experience of their immediate team members and across external contacts, including staff in other ACI roles (e.g. systems administrators, software specialists, etc.). The final portion in this chapter discusses the importance of leveraging contacts of other researchers and staff when identifying researchers who might benefit from communicating with one another.

Jump to: top

Build Connections around Commonalities

- by Research Domain

- by Computational Methods

- by Software

- by Data Types

- by Professional Roles and Practices

Research Domain

Opportunities to connect researchers pursuing complementary or related research problems will perhaps be the most obvious. For example, a single campus might have medical and psychology researchers studying aspects of brain function, and engineers developing new or existing imaging technologies and analyses. While researchers with obviously overlapping research pursuits are likely to already know of one another, they may not always be aware of each other’s most recent efforts. Surprisingly, researchers working in the same hallway may not even realize opportunities to share practices in using ACI resources. Furthermore, researchers with no prior interaction may end up pursuing new projects that provide new opportunities for knowledge sharing or collaboration.

Computational Methods

Shared research topics and approaches may mean that researchers share computational methods and practices. Additionally, experts developing computational methods (e.g. from the computer sciences, statistics, and mathematics) may be looking for “domain science” problems to apply their methods to. Researchers using similar computational and analytical methods for very different research domains are much less likely to already know about one another. Examples of methods that cross-cut across disciplines and that have been observed in disparate ACI-using groups include:

- Markov-chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations - observed in the social sciences, statistics, geosciences, engineering, and beyond

- solving partial differential equations (PDEs) - across the physical sciences

- natural language processing (NLP) - observed in the humanities, sociology, psychology, geosciences, and computer sciences

- RNAseq analysis - observed across various life and medical sciences

- “open research”/"open science” practices - observed across domains

We will discuss the facilitation of multi-member communities, which have been most successful in the case of bringing somewhat disparate researchers together around similar practices that reach across domains, later on in this chapter.

Software

There are a large number of cases for which the same software and programming languages may be used by researchers who might connect around their use of ACI. For example, MATLAB, Python, and R are frequently used for programming across research domains, and some campuses have formed communities around these languages. These may be further tied to a general research area (e.g., “R programming in biology”) for which the same modules or libraries are frequently used. Beyond programming languages and practices, researchers using the same third-party software may also benefit from connecting. For example, some software for working with genetic sequences will be used across a wide range of biological research areas. Research groups using the same computational chemistry software may benefit from sharing methods for optimizing the software performance on specific ACI systems. When research groups across domains use commercial software with licenses that are not supported by the campus, these researchers may benefit not only from sharing software use practices for but also for sharing licenses (e.g. Comsol, which is used across a number of research domains for physical simulations).

Data Types

Researchers may also find commonalities and share practice around common data formats, methods for producing or using similar data, or even the use of data from the same sources. For example, researchers in the humanities, geology, and social sciences (psychology, communication, etc.) may be able to share practices or even costs for obtaining and analyzing data from social media (e.g. Twitter). Similar opportunities may exist across research domains that rely on global information systems (GIS) data, such they they will benefit from sharing access, analysis, and visualization practices. Facilitators might even help to coordinate the support of a single, shared repository of large datasets, perhaps on an ACI resource with which the facilitator is associated, so that researchers do not have to maintain separate, redundant copies for themselves.

Professional Roles and Practices

Facilitators might also be able to connect individuals — researchers and support staff — based upon professional roles. Research students and staff who support research systems or who develop software and computational workflows may benefit from sharing practices across research units on a single campus. For example, the University of Wisconsin-Madison has successfully formed a group for research systems administrators, whose roles often require solutions that are heavily matched and integrated with research processes. In the chapter on Interfacing with Other ACI Personnel, we will discuss additional strategies for networking with individuals in other ACI and IT positions to enhance the ability of all individuals to meet researcher needs, and to enhance the professional development of the Facilitator.

Of course, researchers may share more than one of the above in common, in which case there may be even greater potential for productive knowledge exchange and collaboration.

Jump to: top

Encourage Self-Sustaining Connections

Overall, the goal of the facilitator should be to encourage researchers and other participating individuals to leverage the expertise of others and to sustain a connection for as long as is beneficial to those involved. Some connections may only need one communication or meeting instance for participating parties to gain sufficient understanding and impact from one another. Furthermore, interactions suggested by a facilitator may not necessarily lead to a fruitful exchange or be perceived by participants as worthwhile into the future, for a number of reasons that are out of the control of the facilitator. For example, a facilitator might incorrectly perceive that the methods of two research groups are similar, or groups with very similar research interests and computational methods may see each other more as competitors. Therefore, a facilitator maintaining some role in this process should take into account participant perceptions and expectations when determining when and how best to encourage future interactions. If there are logistical barriers, such as busy participant schedules or long distances for in-person meetings, the facilitator might suggest approaches that better enable communication in these circumstances (e.g. virtual meetings, less frequent meetings, email follow-ups, etc.).

Jump to: top

Coordinate Knowledge Exchange Between Researchers

Perhaps the most natural and frequently impactful connections are one-to-one or one-to-many interactions between researchers for the purpose of technology exchange. For example, a facilitator might match a new user of an ACI resource with an existing user who has already deployed the same software or computational approach. If the two researchers are also from similar research domains or the same research group and, therefore, share a similar vocabulary, they’ll likely communicate and learn from each other even better than from the facilitator (see discussions and references on peer-learning in Education and Training of Researchers). To some extent, knowledge exchange between peers can be a crucial component of the assistance and education of individual researchers, and in a way that scales beyond the facilitator’s own efforts.

After realizing that such a connection might be beneficial, the facilitator should obtain permission from both parties before providing a formal introduction. Depending on the context, the facilitator might even join a first meeting or remain CC’d for email discussions - an approach that can be important for ensuring best practices and correcting initial misinformation. Generally, the facilitator should step back after communication productively kicks off, but reiterate the availability of any needed support and assistance, including participation in any future discussions. Even when two researchers have other, non-ACI-specific research aspects in common (e.g. non-computational methods, model organisms, etc.), a facilitator may mention these similarities and enable conversations between researchers who might not have heard of one another. In this situation, the facilitator’s role may simply be to introduce the work of one researcher to another.

Importantly, the facilitator might work with knowledgeable individuals with demonstrated success to create online documentation and other shared training materials. Individuals with similar software or methods might benefit from participating in group meetings or an email list, as described below. The facilitation of formal and informal collaborations is covered later in this chapter, but may also be an outcome of initially connecting researchers based upon similarities in research and ACI practices.

Jump to: top

Promote the Formation of Communities

For some instances where a facilitator sees the potential for fruitful, repeated interaction among individuals, it may be appropriate to form a community or group around common interests, including any of the previously described topics. For example, the facilitator may increasingly connect researchers in communication around the same topic, and see a benefit of an email list or regular meetings to facilitate group discussions and technology exchange. Researchers may even come to facilitators or similar staff to discuss the potential for a specific group they have in mind, or to request assistance in initiating and promoting the group.

The most fruitful  communities and groups may be those for which

researchers assemble around interests that reach beyond the limits of

individual departments and other academic boundaries. As previously

described, campus groups have been formed around specific statistical

methods, common software, reproducible programming practices,

computational genomics, and digital humanities, among other topics that

span departments and disciplines. Experience from ACI-REF member

institutions has also indicated significant benefits for group

participation when these groups are member-organized rather than

facilitator-organized. Therefore, several steps by which a facilitator

may help to initiate and contribute to a community/group are described

below.

communities and groups may be those for which

researchers assemble around interests that reach beyond the limits of

individual departments and other academic boundaries. As previously

described, campus groups have been formed around specific statistical

methods, common software, reproducible programming practices,

computational genomics, and digital humanities, among other topics that

span departments and disciplines. Experience from ACI-REF member

institutions has also indicated significant benefits for group

participation when these groups are member-organized rather than

facilitator-organized. Therefore, several steps by which a facilitator

may help to initiate and contribute to a community/group are described

below.

Jump to: top

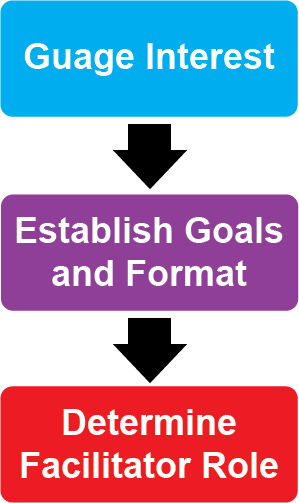

Gauge Interest

To support the initial formation of a community or group, the facilitator and any interested individuals should first leverage their existing interpersonal networks to identify potential group members. Making contact with potential members will help to determine whether forming a group will be perceived as worthwhile by a critical number of participants and will inform how to proceed with the remaining steps. For example, the facilitator might review notes kept from researcher engagements to identify researchers with common interests and then contact them to determine if they also see potential benefits from group discussion. The facilitator could then assist interested individuals in gathering together for a first meeting that addresses the next step.

Jump to: top

Establish Group Goals and Format

Once together, the individuals who have expressed interest should then discuss the goals and topic(s) of focus for the group, perhaps in conversations initially facilitated by the facilitator. Furthermore, the group should decide logistics, such as meeting frequency and duration, in-person vs. virtual interaction, location, whether to define meeting topics each time, and the mode of communication (e.g. email lists, calendar invites, etc.). Ideally, the group will also identify a point person, multiple individuals, or a rotating individual to coordinate meetings and facilitate group discussion. Some groups may simply meet on a monthly basis with a very casual topic discussion format and simple reminder email.

Jump to: top

Facilitator Participation

The facilitator’s role and future participation should also be discussed, recognizing the benefits of leadership by a community member that is not the facilitator, so that the group remains impactful to the participants in both content and format. That said, some groups may benefit significantly by having a facilitator at least present (either regularly or on occasion), especially if the uniting topic of the group is closely related to the use of ACI resources with which the facilitator is associated.

Regardless of ongoing participation in the group, there are a number of ways the facilitator or relevant ACI organization might support communities and groups. For example, the facilitator may assist with organizational logistics (e.g. meetings, email lists, web site), or help to integrate demos of ACI resources into meetings, if relevant. The facilitator can also help promote the group to potential new members, perhaps via established pathways for disseminating information about ACI-related opportunities and events, as mentioned in previous chapters.

Jump to: top

Formal and Informal Collaborations

The most transformative impacts of connecting researchers may come from formal and even informal collaborations, where researchers directly enable each other’s research processes beyond the sharing of practices and peer-learning. Most commonly, collaborations may naturally result from knowledge sharing and communities where the facilitator has already played a prior role in liaising initial interactions, such that little additional action is required unless requested by the researchers.

Without prior connection, researchers might specifically ask a facilitator if she is aware of anyone to collaborate with for the purpose of achieving a specific research goal. For example, researchers in computation- and methods-heavy fields (e.g. computer sciences, engineering, mathematics, statistics, etc.) may be looking for a domain specialist for application; conversely, researchers with domain expertise might seek to work with a computational specialist or engineer to help advance their research. For such a researcher-requested collaboration contact that reaches outside of a researcher’s own domain, identifying collaborators at other institutions should be considered if there are no obvious intra-institutional options.

Researchers might also request to collaborate specifically with the facilitator’s home organization or with another ACI campus provider, especially when research goals require significant use of ACI resources or intimate integration with specific ACI configurations. In these cases, the facilitator may serve the additional role of bringing in other ACI staff or matching the researchers with contacts in other organizations. These participating individuals might also contribute to funding proposals or letters of collaboration. Collaborations with ACI providers may also include partial funding for personnel in the ACI organization, including Facilitator time on specific activities for the project, where this model may be important for long-term financial support of staff in the ACI-providing organization.

Jump to: top

Utilize Relationships with Other ACI Staff

Especially for the purpose of enabling collaborations, facilitators may find that their own professional network of other ACI staff are important for finding researchers with common ACI interests and for supporting existing connections. For example, the facilitator might leverage connections at other institutions to identify a collaboration opportunity for a local researcher. Or, a newly-formed group might request the one-time attendance of staff from another ACI (or non-ACI) organization within the facilitator’s network. For example, a group that meets to compare their computational genomics approaches might like to hear about emerging virtual server options provided by an ACI service that the facilitator does not directly represent. In the case of multiple facilitators at the same institution or ACI organization, this may mean that facilitators regularly communicate about researcher interests in order to share knowledge and identify collaboration opportunities. The next chapter on Interfacing with Other ACI Personnel covers the importance of building a professional network of other staff, both intra- and inter-institutionally, to more holistically support researcher needs.

Jump to: top